The tendency to lose control is not due to children absorbing the aggression involved in the computer game itself, as previous researchers have suggested, but rather to the damage done by stunting the developing mind.

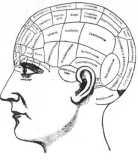

Using the most sophisticated technology available, the level of brain activity was measured in hundreds of teenagers playing a Nintendo game and compared to the brain scans of other students doing a simple, repetitive arithmetical exercise. To the surprise of brain-mapping expert Professor Ryuta Kawashima and his team at Tohoku University in Japan, it was found that the computer game only stimulated activity in the parts of the brain associated with vision and movement.

In contrast, arithmetic stimulated brain activity in both the left and right hemispheres of the frontal lobe - the area of the brain most associated with learning, memory and emotion.

Most worrying of all was that the frontal lobe, which continues to develop in humans until the age of about 20, also has an important role to play in keeping an individual's behaviour in check.

Whenever you use self-control to refrain from lashing out or doing something you should not, the frontal lobe is hard at work.

Children often do things they shouldn't because their frontal lobes are underdeveloped. The more work done to thicken the fibres connecting the neurons in this part of the brain, the better the child's ability will be to control their behaviour. The more this area is stimulated, the more these fibres will thicken.

The students who played computer games were halting the process of brain development and affecting their ability to control potentially anti-social elements of their behaviour.

'The importance of this discovery cannot be underestimated,' Kawashima told The Observer .

'There is a problem we will have with a new generation of children - who play computer games - that we have never seen before.

'The implications are very serious for an increasingly violent society and these students will be doing more and more bad things if they are playing games and not doing other things like reading aloud or learning arithmetic.'

Kawashima, in need of funding for his research, originally decided to investigate the levels of brain activity in children playing video games expecting to find that his research would be a boon to manufacturers.

He expected it to reassure parents that there are hidden benefits to the increasing number of hours their children were devoting to computer games and was startled by what he discovered.

He compared brain activity in children playing Nintendo games with those doing an exercise called the Kraepelin test, which involves adding single-digit numbers continuously for 30 minutes.

The students were given minute doses of a radioactive pharmaceutical through an intravenous drip which allowed a computer to map a complex picture of their brains at work. A subsequent study was conducted using magnetic resonance images.

Both studies confirmed the high level of brain activity involved in carrying out simple addition and subtraction and that this activity was particularly pronounced in the frontal lobe, in both the left and right hemispheres.

Though it is often thought that only the left hemisphere is active for mathematical work and that the right hemi sphere is stimulated by more creative thinking, the professor found that arithmetic produced a high level of activity in both hemispheres.

In subsequent studies, Kawashima established that arithmetic exercises also stimulate more brain activity than listening to music or listening to reading. Reading out loud was also found to be a very effective activity for activating the frontal lobe.

Kawashima, visiting the UK to speak at this weekend's annual conference of the private learning programme Kumon Educational UK, said the message to parents was clear.

'Children need to be encouraged to learn basic reading and writing, of course,' he said. 'But the other thing is to ask them to play outside with other children and interact and to communicate with others as much as possible. This is how they will develop, retain their creativity and become good people.'